The second book I read this summer was about Sophia (didn't seem to have a last name??), the

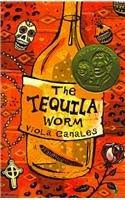

bright child of Mexican immigrants living in a bordertown in the southwest. “The Tequila Worm” by Viola Canales has been

on my list for quite some time, as it is both an award-winner (Pura Belpre) and

another new voice in the growing field of Hispanic literature for teens. Unfortunately, I struggled with this book in

an almost identical way as I did with the Jack Gantos book, “Dead End in

Norvelt.” Both stories are essentially

memoirs that have been fictionalized.

I’m not a fan of the style. I

kind of think that if you are going to write a memoir, you write a memoir. Trying to make a personal story into a

fiction novel leads to many issues which don’t make for strong writing. First and foremost, both Norvelt and this

book have very weak storylines. There is

a general theme of “growing up” but meaning is gathered – and sometimes

stretched – from one disconnected event to another. The tale begins when Sophia is six (?) and

visited by the neighborhood storyteller.

Using a variety of props, she tells Sophia who she is and presents a

tequila worm … the significance of which I never fully figured out (despite its

presence throughout). The book careens

through other moments in Sophia’s life, highlighting struggles that help define

her character. This is another problem

with these books. Because the focus is

on “their life” the main character is often defined by others. The characters around Sophia are clear, but I

couldn’t always see her, only how others reacted to her. It’s as if the author is so much in her own

head that she forgets the reader needs to have the main character as fully

developed as the colorful people who drop in along the way. My additional beefs are minor, but indicative of the

kind of odd focus of these kinds of books.

Bad things are sometimes “smoothed over” and arguments disappear

quickly. Sophia and her mom have a

disagreement near the end of the book which is resolved in a single

paragraph. (Tell me the last time that

ever happened between a mother and daughter!)

There is an over-emphasis on food, with nearly every snack described in

detail. This might be representative of

the culture, but it did make me wonder if Mexican-Americans suffer from

diabetes much. My one take-away was the

“Canicula” – a Mexican-American version of dog days which explains everything

going wrong in the dead of summer. I

have thought of it often in these last few weeks (did I mention a massive tree

branch crashed down outside my window today???)

I continue to seek out Hispanic literature for my students, and this

book, with its specific Mexican-American focus (it also helps to know a little

something about Catholicism), may not suffice. I’ve noticed that these stories tend to focus

on the Hispanic experience of the Southwest.

People of California and Texas may relate to the

tales of Francisco Jimenez, Benjamin Saenz and Canales, but those of us on the

east coast need something different.

Most of our kids hail from El Salvador,

Colombia, and other nations

in central and South America and they tend to

connect with stories that stress urban settings over intact cultural family

institutions that you might find along the border. I think that the works of Judith Ortiz Cofer and E.R.

Frank, for example, are more likely to appeal to my immigrant students than this story. Sorry, this award-winner wasn’t for me.

No comments:

Post a Comment